VIE-Like Structure Affirmed by Supreme People’s Court in China

Saturday, May 6th, 2017, 4:11 pmInvesting in Chinese companies is no easy task, as such investments oftentimes entail complex restrictions imposed on foreign-owned entities, especially in certain restricted industries. To avoid being treated as foreign invested companies, many Chinese companies have opted to set up a contractually owned structure called a Variable Interest Entity (VIE), which allows foreign investors to obtain contractual control right of a domestic Chinese company with the necessary licenses to operate in industries restricted to foreign investors. Many well-known Chinese tech companies, such as Alibaba, Tencent, Youku, and Baidu, have all undergone successful IPOs overseas by using such VIE structure when the IPO market in China was bogged down by heavy regulations. Similarly, Uber entered into China via a VIE structure with a local team and local investment.

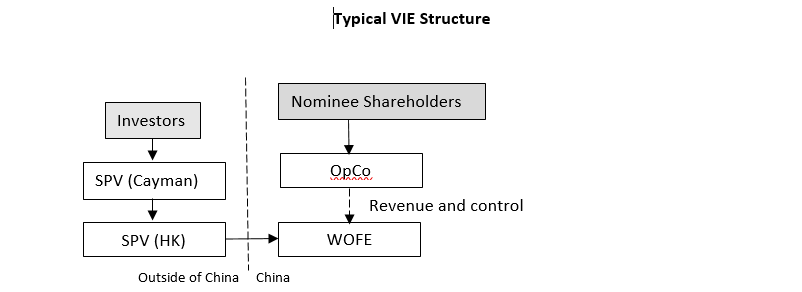

The following diagram illustrates a typical VIE structure often used by Chinese companies to access the overseas capital market and foreign investors. Slight variations of this structure are also used by foreign companies in entering China.

The VIE structure has been a success in the past decade commercially, but it also has certain legal risks, mainly the potential disputes between the legal shareholders (nominee shareholders) and the actual foreign shareholders and the legal enforceability of the various contracts under Chinese law. Chinese law allows a court to invalidate a contract if the purpose of the agreement is illegal. Many commentators pronounced the VIE structure essentially dead after China’s Ministry of Commerce issued a draft Foreign Investment Law for public comment in January 2015. The draft law expressly provided that Chinese domestic companies having no foreign shareholders but “controlled” by foreign investors contractually be subject to the same restrictions as those imposed on foreign invested companies. The draft law even went as far as indicating that the then-existing VIE structures could all be deemed illegal (no grandfather rules) unless special exemptions are granted on a case-by-case basis if the Foreign Investment Law is adopted.

The VIE structure indeed seemed to lose its luster, especially among Chinese companies, due to the ease of the IPO flow by Chinese regulators and the launch of the New Three Board (OTC equivalent market). Many Chinese companies with existing VIE structures commenced the process of converting back to domestic companies in order to apply for domestic listing or fund raising. Moreover, the recent restrictions on the outflow of RMB in China have further accelerated this trend as fewer Chinese companies now have the ability to raise sufficient capital from foreign investors without resorting to RMB-sourced funding in China. After all, with few exceptions, most Chinese companies are still relying upon Chinese investors for financing.

The VIE structure, however, did not die as many have thought, at least not yet. As the legislative process of the Foreign Investment Law is moving rather slowly, the legality of the VIE structure, especially existing ones, remain a hotly debated issue amongst Chinese legislators. In a recently published case, the Supreme People’s Court of China actually surprised many legal scholars with its finding that the framework agreement between a domestic education institution and Ambow Education, a domestic operating entity under VIE control by foreign investors, was valid.

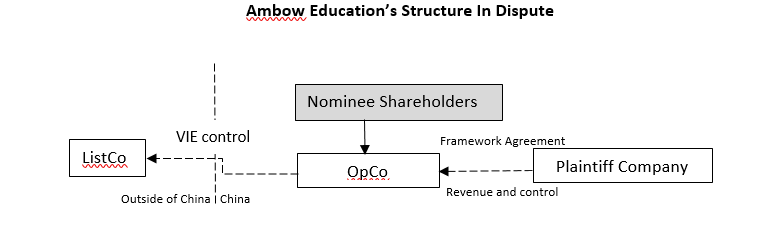

Foreign investment in education industry is restricted in China. When Ambow Education, a provider of educational and career enhancement services in China, got listed on the NYSE in 2010, its Chinese operating entities were controlled by a VIE structure similar to the one illustrated above. Ambow Education, however, did not stop with just one operating entity in China. Before it went public, its Chinese operating entity entered into a series of transactions to purchase the control right and revenue from other Chinese educational institutions for lump sum payments. The plaintiff of the case entered into such a framework agreement with Ambow Education’s Chinese operating entity in 2009. The structure is illustrated below:

The framework agreement reviewed by the Supreme People’s Court in the Ambow Education case is very similar to the framework agreements often used in a VIE structure whereby a domestic company typically transfers its control rights and revenue to another foreign entity or foreign owned entity contractually (the agreement between the OpCo and WFOE in the VIE illustration above). Nevertheless, the Supreme People’s Court drew a distinction between the transfer of controlling rights of a domestic company to another domestic company that is under VIE control of a foreign entity (i.e., the OpCo) and the typical VIE structure where the control rights and revenue of a domestic company get transferred directly to a foreign owned entity. The Court found that the foreign investors of Ambow Education did not assert improper influence on its Chinese operating entity’s operations during its five-year control, and, therefore, in the absence of applicable administrative prohibition of transferring contractual control rights or revenue from one Chinese entity to another, the framework agreement cannot be invalidated solely based on the indirect equity holdings by foreign investors.

Although Chinese courts do not need to follow case law precedents, including the Supreme People’s Court’s rulings, the Ambow Education ruling offers useful guidance on how to create a "safe harbor" for a contractual control and the revenue transfer arrangement. Thus, a similar contractual control and revenue transfer agreement is more likely to be upheld by a Chinese court going forward if (a) another Chinese domestic company is the recipient of such control rights and revenue; (b) the arrangement does not trigger any national security concern; (c) there is no material operational interference from the foreign investors that is prohibited by applicable law; and (d) there is no administrative prohibition of such contractual transfer of control rights and revenue in the relevant industry.

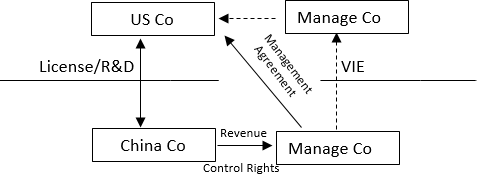

The Ambow Education ruling does not expressly address the validity of the existing VIE structures as of today. However, the reasoning of the Supreme People’s Court indicates that it is more likely that a typical VIE contract would be found valid by a court if all of the “safe harbor” conditions are satisfied. Barring a complete elimination by the Foreign Investment Law in the future, such safe harbor can be a powerful tool for foreign-based investors or companies who are seeking financial returns in the Chinese market for their intellectual property rights or products but are less interested in operational control. As most foreign companies do not have the local expertise and resources to operate in China directly, they can use the contractual control and revenue transfer arrangement to delegate the management of its China business to professional management companies located in or outside of China while retaining certain control rights and revenue consolidation. The management company will in turn manage an operating entity in China with necessary licenses and permits that are otherwise unavailable to companies with direct foreign equity control. By having a local management company as the recipient of the control rights and revenue, the transferring mechanism falls squarely under the Ambow Education ruling, and therefore is more likely to be upheld if challenged.

A sample structure of such a safe harbor arrangement is illustrated as follows:

张宁

合伙人

电话

+16509990227

传真

+15168218978

nzhang@reidwise.com

张伟

电话

+1 2128589968

传真

+15168218978

目录: 文章